Inside The Thriving Industry Of AIDS Orphan Tourism

The global perception that sub-Saharan Africa is experiencing a burgeoning ‘AIDS orphan crisis’, coupled with growing trends in volunteer tourism as reported inTime of 26 July [2007] (Vacationing like Brangelina), has produced a potentially high-risk situation for already vulnerable young children in the region, asserts LINDA RICHTER.

Introduction

The term ‘AIDS orphan tourism’, describes tourist activities consisting of short-term travel to facilities, primarily in sub-Saharan Africa, that involve volunteering as caregivers for ‘AIDS orphans’.

In recent decades, the tourism industry has thrived, grown and diversified to encompass a wide array of travel activities, with alternative volunteer tourism leading the way. Well-to-do tourists enrol for several weeks at a time to build schools, clean and restore river banks, ring birds and other useful activities in mostly poor but exotic settings. AIDS orphan tourism has become a niche market, contributing to the growth of the tourism industry.

AIDS orphans ‘have economic valence’ and ‘orphanhood is a globally circulated commodity’, as some researchers have phrased it.

Well-to-do tourists enrol for several

weeks at a time to build schools, clean and restore river banks, ring birds and other useful activities in mostly poor but exotic settings.Orphans As Commodities

Human beings and their contexts make up landscapes that tourists want to visit through the meanings ascribed by visitors and tour operators. In this case, southern Africa is represented as a place where ‘outside’ volunteers are needed to help countless abandoned children by sustaining charitable operations and giving love and support to desperate young children.

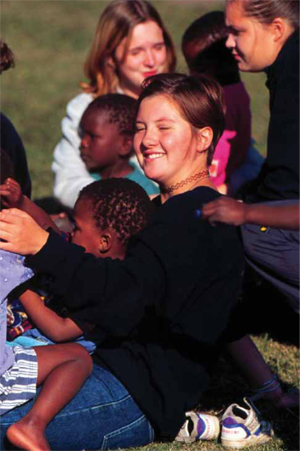

‘AIDS orphan tourism’ is one aspect of the global ‘voluntourism’ industry and an emotional connection with needy young children is at the core of what voluntourists want to experience.

Copyright © Blue Ventures, All Rights Reserved In general, the flow of volunteer tourists tends to be from the global North to the global South, with all age groups participating. Volunteer tourism is a burgeoning industry, and searches for such holidays online and in bookshops unearth a staggering array of options. Travellers can add between a week or a month to their pleasure itineraries to work on a range of projects.

Concern about these forms of volunteering have been raised in recent years by academics, activists, and volunteer organisations. Because ‘voluntourist’ contributions are often brief, the work that can be done is usually low-skilled. As a result there is a real danger of voluntourists crowding out local workers, especially when people are prepared to pay for the privilege to volunteer.

Further, volunteer work is costly to host organisations because of the large overheads needed to host voluntourists. One often-cited report in the international media warned that gap-year students in the UK risked ‘becoming the new colonialists’, with organisations increasingly catering to the needs of volunteers rather than the needs of the communities

they claim to support.The ‘AIDS-Orphan’ Travel Experience

…there is a real danger of voluntourists

crowding out local workers, especially when people are prepared to pay for the privilege to volunteer.As in other countries undergoing social or other changes, non-family residential group care (orphanages) in southern Africa has expanded, perversely driven by the availability of funds for such facilities, and the glamour that media personalities have brought to setting them up. However, many orphanages are not registered with welfare authorities as required by law, and most face funding uncertainties and high staff turnover, making them unstable rather than secure environments for children. Moreover, children taken in by orphanages are usually from desperately poor families rather than orphans – the case of David Banda in Malawi is a case in point.

Copyright © Blue Ventures, All Rights Reserved Under the misapprehension that volunteers will benefit children, some residential care facilities have opened up their institutions to global volunteers for short periods of time. Young people are targeted, some by commercial operators, to seek personal fulfilment through encounters with destitute and disadvantaged children. In some instances, intermediary organisations might link affluent travellers with local organisations for the purpose of conscientising and fund-raising.

Volunteers Come At A Cost

Programmes which encourage or allow short-term tourists to take on primary care-giving roles for very young children are misguided for a number of reasons. Volunteers come at a cost: institutions frequently provide voluntourists with accommodation and meals, and staff are allocated to guide volunteers around and organise their activities.

Given the level of unemployment and poverty among young people in many parts of sub-Saharan Africa, and their desperate need for training and work skills, these opportunities should best be given to local youth, many of whom would be grateful for regular meals, some training and a testimonial to their work experience.

Adverse Emotional and Psychological Effects

Volunteers come at a cost; institutions

frequently provide voluntourists with

accommodation and meals, and staff are

allocated to guide volunteers around and

organise their activities.Aside from economic and employment questions, there are serious concerns about the impacts of short-term caregivers on the emotional and psychological health of very young children in residential care facilities. The formation and dissolution of attachment bonds with successive volunteers is likely to be especially damaging to young children. Unstable attachments and losses experienced by young children with changing caregivers leaves them very vulnerable, and puts them at greatly increased risk for psychosocial problems that could affect their long-term well-being.

Consistently observed characteristics of children in institutional care are indiscriminate friendliness and an excessive need for attention. Children in orphanages tend to approach all adults with the same level of sociability and affection, often clinging to caregivers, even those encountered for the first time only moments before. Children in more orthodox

family environments of the same age tend to be wary towards newcomers, and show differential affection and trust towards their intimate caregivers and strangers.

Copyright © Blue Ventures, All Rights Reserved Institutionalised children will thus tend to manifest the same indiscriminate affection towards volunteers. After a few days or weeks, this attachment is broken when the volunteer leaves and a new attachment forms when the next volunteer arrives. Although there is little empirical evidence on children’s reactions to very short-term, repeat attachments over time, evidence from the study of children in temporary or unstable foster care indicates that repeated disruptions in attachment are extremely disturbing for children, especially very young children.

Short-term volunteer tourists are encouraged to ‘make intimate connections’ with previously neglected, abused, and abandoned young children. However, shortly after these ‘connections’ have been made, tourists leave – many undoubtedly feeling that they have made a positive contribution to the plight of very vulnerable children. And, in turn, feeling very special as a result of receiving a needy child’s affection. Unfortunately, many of the children they leave behind have experienced another abandonment to the detriment of their short- and long-term emotional and social development.

…many of the children they leave behind have experienced another abandonment to the detriment of their short- and long-term emotional and social development.

Voluntourism is potentially exploitative of children suffering adversity as a result of poverty and HIV/AIDS. Child advocates should protest these practices and welfare authorities should ensure they are stopped. Thus far, no formal regulations exist in any sub-Saharan African country to protect children from such practices. The weight of current evidence suggests that these activities are not in the best interests of children and those working to protect children and

children’s rights should be deeply concerned.

About Professor Linda Richter, PhD

Families Are Best

Historically, residential care has increased during periods of social change and crisis – colonialism, communism in Eastern Europe, wars and natural disasters. HIV/AIDS also constitutes a crisis, but it is a long-wave event, and the first line of response should be to support those who can look after children best – their own families. Instead, some international agencies, donors, and local groups are contributing to the ever-increasing number of orphanages being

established for children affected by poverty and HIV/AIDS.Together, a lack of support for families, increasing institutionalisation of vulnerable children, and a growing international volunteer tourism industry are placing very young affected children at increased risk.

The important points are these:

- Every available resource should be utilised to support families and extended kin to enable them to provide high quality care for their children. Out-of-home residential care should not be an option when support can be given to families to take care of their own children.

- Children out of parental care have a right to protection, including against experiences that are harmful for them. In particular, they have a right to be protected against repeated broken attachments as a result of rapid staff turnover in orphanages, exacerbated by care provided by shortterm volunteers.

- Welfare authorities must act against voluntourism companies and residential homes that exploit misguided international sympathies to make profits at the extent of children’s well-being.

- Lastly, well-meaning young people should be made aware of the potential consequences of their own involvement in these care settings, be discouraged from taking part in such tourist expeditions, and be given guidelines on how to manage relationships to minimise negative outcomes for young children.

This article is based on Richter, L. & Norman, A. (2010) ‘AIDS orphan tourism: A threat to young children in residential care’, in Vulnerable Children and Youth Studies (in press).

P

P